Tuesday 16 October 2007

Wednesday 8 August 2007

Farhangshahr = Kulturstaat

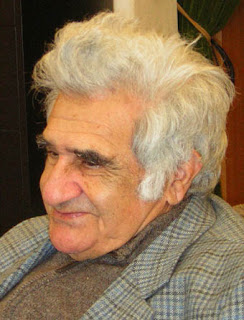

Manuchehr Jamali

„FARHANGSHAHR“

(KULTURSTAAT)

Die Entstehung einer iranischen Gesellschaft auf der Grundlage der eigenen humanen Kultur

Eine erste Skizze zum Thema „Politisches Denken im Iran“

Die iranische Kultur gründet sich fest auf die Idee, dass alle Menschen aus allen Bevölkerungsschichten trotz ethnischer Verschiedenheit, ob sesshaft oder Nomade und ganz gleich welcher Religion, politischen Richtung oder Ideologie, sich in den Wunsch teilen, ihr gemeinsames Leben durch die menschliche kreative Vernunft (kherad) zu gestalten und miteinander über die Entwicklung ihrer Gesellschaft in der heutigen Welt nachzudenken. Die Heiligkeit des menschlichen Lebens ist das höchste Prinzip in der Kultur des Iran und daraus folgt als erstes Prinzip für die Bildung unseres Staates die Teilhabe aller am gemeinsamen Dialog (hamporsi) auf der Suche nach der bestmöglichen Form des Zusammenlebens. Argumente und Beweise für eine Religion, Ideologie oder Denkrichtung im Sinne des „privilegierten Wahrheitsbesitzers“, die dann zur Bestätigung und Propagierung von politischen Programmen oder sogar als Grundlage von Staat und Gesellschaft benutzt werden, sind der iranischen Kultur fremd. Ein solches Vorgehen würde gegen das iranische Gottesverständnis verstossen, denn hier ist die Gottheit gleichen Ursprungs mit dem Menschen: das Prinzip des Suchens, Forschens, experimentierenden Erprobens ist Eigenheit des Göttlichen im Iran und im Menschen selbst liegt der Ursprung des Neuen. Von dort kommen Innovation und gesellschaftliche Initiative und wenden sich gegen die Endgültigkeit des wahren Glaubens oder der einzig richtigen Schulmeinung und Ideologie.

Das iranische gesellschaftliche Zusammenleben ruht fest und sicher auf der Grundlage der menschlichen Vernunft aller. Das Miteinander im Prozess des kreativen Denkens ermöglicht den Schutz und das Fördern des Lebens der Gemeinschaft. Die Kultur des Iran betrachtet die Heiligkeit des Lebens als Urquelle der gesellschaftlichen Ordnung. Für die Kultur des Iran ist die kreative Vernunft (kherad) das Auge der Seele und des Lebens. Die menschliche Vernunft wird aus der lebendigen Tiefe des irdischen Menschen geboren und ihre Aufgabe ist die Pflege und der Schutz des Lebens aller Menschen in dieser Welt ohne Ansehen der Person. Ordnunggebendes (samandeh) Prinzip ist eine Vernunft, die aus dem „Leben auf dieser Erde“ hervorquilt. „Saman“wie „khashtara“ - das „shahr“ entspricht – bedeutet „hokumat“ (Rechtsstaat). Aus der menschlichen Vernunft erwachsen Staat, Gesetz und politische Ordnung. In jedem Menschen wohnt die schöpferische, ordnungspendende Vernunft (kherad), d.h. die Fähigkeit zum Staat, Gesetze und soziale Gemeinschaft schaffenden eigenen Denken. Die Gottheit BAHMAN, die die ordnungspendende Vernunft - griechisch „arke“- oder das „Prinzip der Ordnung“ personifiziert, lebt in jedem Menschen als Gottheit „ARTA“. BAHMAN manifestier sich als „ARTA“, die Gesetz, Recht und Gerechtigkeit repräsentiert. Mit anderen Worten Recht, Gesetz und Gerechtigkeit sind Phänomene geboren aus der ureigenen Vernunft des Menschen.

BAHMAN, der die kreative Vernunft jedes Menschen darstellt, wandelt sich im Kontext der sozialen Gemeinschaft zum Prinzip des gemeisamen Befragens (hamporsi), des Mischens, der Harmonie und des sozialen Zusammenhalts der Menschen untereinander. “Hamporsi“ ist der nie endende Dialog. Der Mensch in seiner Ursprünglichkeit befindet sich in permanenter Auseinandersetzung (hamporsi) mit dem Göttlichen und seine Einsicht (binesh) kommt aus dem unmittelbaren Fragen, Be- und Gegenfragen (hamporsi) des eigenen und allgemein Göttlichen. Der Mensch steht im Dialog (hamporsi) mit dem Göttlichen. Mit dieser Definition als Vorausetzung ist der Dialog der Menschen untereinander immer auch „hamporsi“ mit dem Heilig-Göttlichen. Der iranische Kulturstaat (farhangshahr) geht von der „Gleichheit aller Menschen“ aus, denn alle Menschen haben Teil an dem einen „Leben“ (jan), alle Menschen sind Samen des Lebensbaums d.h. sie sind göttlich, sie sind in ihrer Gesamtheit „janan“ (All-Leben). Da die kreative Vernunft (kherad) aus diesem heilig-göttlichen Leben (jan) unmittelbar hervorgeht (tarawesh) , sind „Leben und Vernunft“ jedes Menschen heilig. Kein Gesetz, keine Macht und kein Gott hat das Recht, dem Leben oder der menschlichen Vernunft Gewalt anzutun. Der Vernunft in ihrem kreativen Denken die Freiheit zu nehmen ist Vergewaltigung des Lebens und Negierung der Ursprünglichkeit des Menschen.

Auf diese Weise sind Freiheit der menschlichen Vernunft und kreatives Denken im Selbstverständnis der Kultur des Iran heilig. Der Begriff „shahriwar“, der über Jahrtausende die Werteskala der politischen Macht des Iraners bestimmte, definiert sich als „Herrscher und Staat gewählt durch die kreative Vernunft der Menschen“. Regierender und Regierter müssen immer wieder mit Hilfe der menschlichen Vernunft (kherad) von neuem frei gewählt werden und nicht nach „Glaubensgrundsätzen“, die die fertige Idee der „absoluten Wahrheit“ präsentieren, und die sich gegen die suchende, forschende, neuschaffende Natur des Menschen wenden. In der Kultur des Iran sind die Menschen wie Samen einer Traube (khusheh), deren Weinbeeren durch die Rispen miteinander verbunden sind. Die Traube (khusheh) als Gesamtheit aller potenziellen Samen ist Sinnbild des Göttlichen. Eingebundensein und beständiger Dialog (hamporsi) charakterisieren das Miteinander des Einzelnen mit dem Ganzen. Mit anderen Worten, das Individuum handelt gemäss den iranischen Vorstellungen vom Göttlichen, wenn es sich mit anderen Individuen in einem demokratischen Rechtsstaat organisiert. Eine funktionierende soziale Gemeinschaft (wahdat-e ejtema`) wächst heran durch den Diskurs des Einzelnen mit den Anderen in der Suche nach einer angemessenen Form des Zusammenlebens und nicht durch den „Glauben an einen Führer, eine Religion, eine Lehre oder ein ´Heiliges Buch`“. BAHMAN und ARTA in der Tiefe jedes Menschen symbolisieren Ursprung des Anfangs und des Neuschaffens.

Die Jahrtausende alte Kultur des Iran, die tief in der Seele und im Herzen des Iraners verwurzelt ist, wird die Gründerin unseres neuerblühenden (nauawar) Staates und unserer Gesellschaft sein. All diese wohlklingenden Worte wie Zivilgesellschaft (jame´eh-madani), Menschenrechte, soziale Gerechtigkeit, repräsentative Demokratie (mardomsalari) oder Modernismus, die die muslimischen Intellektuellen vom Westen lernten, bleiben für uns im Kontext des Islam leere Begriffe, denn sie haben hier keine ursprünglichen Wurzeln, und eigentlich auch nicht im Judentum und Christentum. In Europa wurden sie durch die Renaissance aus der griechischen Kultur übernommen und als Konsequenz dieser Wiedergeburt oder dieses „Frischwerdens“ (fereshgard) wurde das Fundament für die moderne Welt des Westens gelegt. Wir sind die Initiatoren unserer eigenen Renaissance (fereshgard) und stehen mitten im Gährungsprozess unserer kulturellen Urelemente, um schliesslich das Fest der Entstehung eines neuen Staates und einer neuen Gesellschaft in der Wiedergeburt unserer ursprünglichen kulturellen Werte und im Jungwerden unseres Volkes zu feiern.

Monday 6 August 2007

Gott und Mensch

MENSCH: DER AUSWÄHLENDE UND ORDNEND VERBINDENDE

Jener, der erschafft,

schafft im Übermass.

Aus Freude am brodelnden Schöpfungsakt

zeugt er zeitlos Neues.

Mitnichten sieht er das Fremdsein der Geschöpfe zueinander.

Am Ort seiner Schöpfungskraft

zeigt sich das Chaos.

Seit dem Tag, an dem der Mensch den Schritt in die weite Welt tat,

quälte ihn

das Chaos.

Zur Rettung aus diesem Chaos göttlicher Kreation

fiel seine Wahl auf Teile.

Zusammenfügend

baute er geordnete Welten.

Heimisch nun liess er sich darin nieder.

Aber das Chaos blieb, was es immer war.

Die Menschen wählen nach Wunsch

aus diesem endlosen Speicher des Chaos.

Sie fügen zusammen, ... .

Doch wie ein Meer ohne Ufer ist die Weite des Chaos,

umspült die verständig geordneten Inselwelten, die Bauten der Menschen.

Der Ordnung schaffende Verstand des Menschen

kehrt dem schöpferischen Gott noch immer den Rücken zu, Rache schwörend.

Auch die den Gott Liebenden

sehen nur einen Gott, der kein Chaos kennt,

fühlen sich wohl in den Engen selbst gewählter, überschaubarer Ordnung.

Besässe Gott ihren Verstand, nie würde er zum Schöpfer.

Der Verstand sucht die Enge der Ordnung.

Das Schöpferische aber lebt lustvoll mit dem endlosen Wachsen des Chaos.

Mich wundert, warum es heisst:“ Gott schuf sich den Menschen zum Bilde... .“

und wie der Mensch dachte, er schüfe selbst sich Gott zum Bilde.

Manuchehr Jamali, „KARIZ“, London 1994 (S. 62-63).

Sunday 5 August 2007

Der klavierbauer und die Guillotine

Das stürmisch grosse Spektakel der französischen Revolution

faszinierte das Auge noch jedes Betrachters.

Doch ein Detail am Rande des Geschehens, nahezu unbeachtet,

wirft Licht auf das Dunkle in Leben, Geschichte und Wahrheit:

Die erste Guillotine baute ein Klavierbauer.

Finger, die über Tasten glitten, lösten die schlagende, schneidende Klinge.

Die Idee vom tödlichen Schnitt ersetzte im Nu den Gedanken des Liebkosens

und der Gott der Musik wurde zum mörderischen Abgott.

Als Sinnbild offenbart es hunderte unglaubliche Phänomene.

Zwischen den Zeilen der unzähligen Sufi-Liebeslieder

half es mir erkennen, dass der Gott der Liebe die erste Hölle schuf.

Meine Augen, entzückt von des Predigers Wort über Mitleid und Erbarmen

auf Erden,

öffnete es und voll Betroffenheit sah ich, wie jener selbst die erste Grausamkeit

beging.

In den dicken Büchern über die Wahrheit,

in deren dunkle Vielschichtigkeit ich mich lange vertiefte, fand ich beim Schein dieses

Sinnbilds

in einem Einwurf zwischen zwei Sätzen

die erste Lüge.

Bei den Besonnenen, -Tag und Nacht priesen sie die Vernunft und dachten- ,

sah ich den ersten Blitz des Wahns in die Welt einschlagen.

Der den Zweifel als Methode lehrte zur Befreiung von altbacknen Theorien...,

in seines Herzens Tiefe erblickte ich die Weberwerkstatt inniger Glaubensbande.

Der über Freiheit reflektierte, -Verlust der Freiheit war seine stete Furcht-,

bei ihm reckte die Tyrannei den Hals im ersten Dämmerlicht.

Der es ernst meinte mit der Last der Sehnsucht nach des `Ewigen Lebens´ Ruh,

fand als erster den Augenblick.

Statt des Jubels über die eigene Ewigkeit

genoss er das Jetzt.

Den das Staunen beglückte,

er lehrte Fremdenhass,

erwog nicht, dass das Unbekannte Erstaunen erregt.

Der die Welt aus Liebe erschaffen wollte,

war der erste Egoist.

Je grösser sein Verzicht,

desto mehr sah er nur sich selbst.

Vor meinem geistigen Auge wird noch immer, plötzlich und ungewollt, das Piano zur

Guillotine,

die Liebkosung zum Todesschlag,

Freundlichkeit zu Gewalt,

Liebe zu Hass,

Gott zu Ahriman.

Ahriman bete ich an wie Gott.

Zum Teufel wird der Gott im revolutionären Wandel.

Voilà..., meine Anbetung setze ich fort unbeirrt,

in der Guillotine sehe ich noch immer das Piano.

Manuchehr Jamali, „KARIZ“, London 1994 (S. 56-57).

Friday 20 July 2007

Kharad-e sarpich dar Farhang-e Iran

Wednesday 18 July 2007

Das unsichtbare Zollhaus

Mein welterfahrener Blick, - kaum verliess er das Auge, kehrte er ins Auge zurück -,

barg die Sicht der Dinge, die er mir zutrug aus weiter Ferne,

schmerzlich verschleiert.

Dankbar war ich ihm

Und verwundert über die Bitterkeit seines Schmerzes:

Unterwegs verweilte er an keinem Ort um zu ruhen,

der Raum zwischen mir und dem Gesichteten war frei,

seine Bewegung schnell, niemand nähme es auf mit ihm, gar schlüge ihm eine Wunde.

Eines Tages ohne sein Wissen, heimlich von Schatten zu Schatten, lief ich ihm nach.

Hinauseilen wollte er aus dem Auge,

als ein Zeichen „Halt“ mit wuchtigem Balken den Weg uns sperrte.

Hier stand das Zollhaus.

Das Blickgepäck, leicht aber umfassend, öffnete der Zöllner mit böser Miene,

zuoberst kehrte er das Unterste des Blicks:

In meinem Blick entdeckte er die mutige Kühnheit von Iblis,

den Zweifel Descartes,

sokratische Ironie,

Obeids entblössenden Spott,

die Lust am Vagabundieren,

Maulanas kraftvolle Faust an Türen klopfend, dass sie sich öffnen,

Djamschids Schlüssel zu den Toren des Verborgenen,

des Falken pfeilschnelle Flügel,

den felsenspaltenden Bohrer.

In meinem Blick strahlte die Liebe zur Welt.

In meinem Blick lag das zarte Kosen klaren Wassers aus süssen Quellen,

die flexible Weichheit im Umgang mit Gegensätzen.

Hafez sah er in meinem Blick und dessen klugen Vogel, den keine Falle fängt.

Meine langen Krallen sah er, die alles ergreifen, was erreichbar.

Er sah in meinem Blick den funkensprühenden Schlund meines Seins

und eine Hand, die auf die Brust der Lüge schlug, die den Namen Wahrheit trägt.

Der Zöllner sagte: „Solche Ausfuhr über die Grenze ist verboten.“

Widerspruch kam: „Der mich schickte, gab mir diese Wegzehrung zur Stärkung.“

Nichts hören wollte der Grenzer:

„Ohn´ all das musst du hinausgehen aus dir.“

Voll Ungeduld war mein Blick, seine Pflicht zu erfüllen.

Im Zolldepot liess er alles mit Beleg,

empfing, was er überlassen, erst bei der Wiederkehr.

Verrottet war alles im Speicher vom Zoll und stinkend.

Verschämt trat er vor mich,

schwieg sich aus übers Abenteuer auf halbem Wege.

Doch was er am anderen Ende des Weges gesehen, trug er vor weitläufig.

An diesem Tag verlor ich das Vertrauen in meinen Blick.

[Maulana Djalal al-Din Rumi (1207-1273) aus Balch, mystischer Dichter; Obeid-e Zakani (?-1371), satirischer Dichter; Hafez-e Shirazi (1325-1389), lyrischer Dichter; Djamschid – mythischer König.]

Manuchehr Jamali, „KARIZ“, London 1994 (S. 4-5); Übers.: B. Burgwinkel, 2007.

Manuchehr Jamali, The Obstinate Iranian Thinker

Manuchehr Jamali's writings cover a wide spectrum of subjects and ideas which are unfolding their outlines vis-à-vis a background of five thousand years or more of Iranian culture summed up by the author as “Farhang-e Simorghi” (Simorgh culture). With diligence and patience he spent the last years consulting dictionaries, encyclopaedias and further philological material together with classical Iranian literature (10th to 15th century A.D.), Zoroastrian texts and other early writings from the pre-Islamic period to re-construct the Simorgh myth, a way of thinking which has given to the people of Iran their unique culture. But there it does not stop. Instead of staying dead historic artefacts his findings provide him with an instrument to approach the problems of present day Iran. With an easy hand he tackles the task of connecting modern thinking with the most ancient Iranian ideas and offers solutions to philosophical, political, social etc. problems which enchant the Iranian readers because here they can observe the process of creative reflection in their own Persian terms and language.

M. Jamali is an advocate of self-thinking and opposed to translations. Translations from foreign languages are a necessity for any modern society, but as long as the new ideas do not become rooted in already existing concepts of the respective people they are lost on them. As an example he cites communism. In Farsi there exist ample translations of all kinds of Marxist literature up to the Frankfurter Schule etc. and even Habermas, one of its last exponents, visited Iran lately causing a lot of public attention. But a discussion about Marxism with an Iranian communist very quickly ends in a cul-de-sac because his believes as a Muslim preceding his Marxist thinking have never been questioned by him. Marxism was simply put on top of everything. M.Jamali argues that a modern liberal democratic Iranian state needs to base itself on Iranian ideas to give the Iranian people an opportunity to really identify themselves with it. The “Farhang-e Simorghi“ is for him the ideal solution.

M. Jamali's first attempts as an independent thinker go back to his early youth when still at school he became interested in Zoroastrianism and wrote a little book about the subject which was even printed. Over the following years further short writings were added although he had to study physics at Teheran University where he finished with success. By the end of the1950s he was already in Germany but his now philosophical studies at the universities of Tübingen, Frankfurt, München and Berlin were marred by financial problems. The next fifteen years seem to have been a time of incubation. When in the second half of the 1970s he spent more time in London he suddenly came into his own and over the years he has published an oeuvre of more then eighty titles, mostly in small or even tiny editions which he financed nearly completely himself. There was only from time to time the odd “murid” (disciple) who sent him some money. Up to now his intellectual development can be divided vaguely into four to five phases. The first phase shows him still deeply steeped in religio- philosophical subjects. The main influence on his writings during this period are Attar and Maulawi, and from among European writers the modern German philosophers Karl Jaspers and Max Scheler, but also Hegel, Nietzsche and the Danish Christian thinker Soeren Kierkegaard. Nietzsche stayed with him as a favourite. His next phase begins with the arrival of Khomeini on the political stage. M. Jamali discovers a “Feindbild”. He writes political articles related to the on-going discussions about the situation in Iran. He even publishes together with a friend his own weekly newspaper although just for a few month. Koran, Bible, Karl Popper, Friedrich A. Hayek, books about constitutional law – this is his most important reading material during that period. With the war going on between Iran and Iraq M. Jamali enters his third phase. He begins a closer study of Firdausi's Shahnameh, and also of Hafez. Plato and the modern German philosopher Ernst Bloch accompany his writing into the fourth phase where he becomes interested in theories of myth and mythology and discovers the female Iranian goddesses as transmitters of ancient Iranian ideas and values. In his momentary phase he is busy defining “Farhang-e Simorghi”, the phenomenon of an ancient Iranian culture the values of which never ceased to exist among the Iranian people.

Highlights of M. Jamali's publications are “Azadi haqq-e intiqad az islam ast” (“Freedom Is The Right To Criticize Islam”), London 1983; “Ateshi keh sho´oleh khwahad keshid” (“A Fire Which Will Blaze Away”), London 1987; “Posht beh su`alat-e mohal” (“Turning The Back On Absurd Questions”), London 1991; “Mafhum-e ¨wara`-e kofr wa din¨ dar ghazaliyat-e Sheikh ´Attar” (“ The Meaning of ¨ Beyond Belief and Disbelief ¨ in Sheikh Attar's Ghazaliyat”), London 1993; “Kariz”, (“Subterranean Water Channel”), London 1994; “Rendi – howiyat-e mo´ama`i-ye irani” (“Rendi – The Enigmatic Iranian Identity”), London 1996; “Maulawi-ye sanamparast” (“Maulawi, The Idolator”), London 2005; “Sekulariteh dar iran ya ´arusi-ye insan ba jehan” (“Secularism In Iran Or Man's Marriage With The World”), London 2006.

“Kariz” is a collection of poems on philosophical themes. M. Jamali is composing poetry perhaps even longer than prose. All kinds of abstract thoughts are transformed by his poetic creativeness into attractively bright and lively images and eventually put down in free verse elucidating his prose by widening the out-look as well as adding a further aesthetic dimension to his work.

M. Jamali's library is extensive. Persian literature, books on Islamic themes and religion in general, works on philosophy covering the development of philosophical thought in the western world and outside from the beginnings up to today, writings on political sciences, sociology, jurisprudence, art and archaeology, etc.. During his extensive travels in Europe and USA M. Jamali collected numerous books on these different fields of study. Apart from Farsi he reads German, English, French and Arabic and he has acquired the necessary knowledge of those languages which are assisting his philological research. Various dictionaries and encyclopaedias supplement and complete the tools for his investigations.

As already mentioned, the Simorgh culture, the “Farhang-e Simorghi” has caught M. Jamali's imagination for the moment. It is becoming such a substantial part of his work as a writer and philosopher that a closer look at some of the basic ideas will also serve as a brief introduction to M. Jamali's own world of thought.

In Iranian culture the concept of “mehr” (love, care) combined with the term “kherad” (creative reason) means a form of social cohesion dominated by the idea of care: care for one another and the community, care for nature, care for life. The basic ideas and imagery of the key terms related to “mehr” and “kherad” are taken from the world of plants and cultivation which might indicate that they were originally conceived by a civilization in harmony and co-operation with nature. Man is thought of as “nay” (cane; flute) or as a “seed” (“tokhm”) from the “tree of life”. A seed naturally implies “growth”: Iranian man is not created by a god but he grows by himself as any other seed. Equally, a seed is surrounded by the “darkness” of the earth and contains in itself a “darkness” (“tokhm dar tokhm”, seed within a seed). “Darkness” and related terms as “ghar” (cave), “cah” (well) or ”zehdan” (uterus) are positive terms. The dark enclosed space is thought of as the origin of new fertility. It means renewal, becoming fresh and new (“fereshgard”).

“Fertility” and likewise “creativity” are conceived as the result of the unification of a pair (“djoft”) including a third party, the “miyan” i.e. Bahman. “Miyan” is a term and concept difficult to define. In Iranian cosmology it is “water or clouds” and “air or wind”, and its image is the wave. Since there is no division between heaven and earth, but everything is only earth or all-life (“janan”) in perpetual process of creation – a thought of far reaching ethical consequences– the “miyan” personified as the divinity Bahman is the invisible “in-between” who not only fills the gap but is the stimulator of new creation in conjunction with “mehr”. In abstract terms he is best defined as the principle of synthesis and intermingling. The yoke (“yugh”) is one of the images of the unified pair, but the general symbol for the idea of “yeki seh tai” (“trinity”) is the “disque (i.e. “tokhm”) with the two wings” which over the centuries changed into the magnificent figure of the bird Simorgh.

Man - male and female are of equal value -, nature and everything existing are part of the holy divine all-life (“janan”) in which “mehr” is omnipresent. For the Iranian life (“jan”) is holy and inviolable because of the immanence of the divine. To this way of thinking the term “transcendence” is foreign and simply not applicable - neither as philosophical nor as theological category. Inherent in the concept of “miyan” is the principle of interrelatedness or interconnection (“peywastegi”) but not in the sense of pantheism or monism. For the Iranian the whole of existence is in motion and in permanent change and he himself is not given to passivity and meditation but is part of the whole and actively participates in it with his reason and imagination.

Iranian man seen as individual is the owner of “kherad” (creative reason). He creates himself as a person (“khod”) and forms his environment guided by the concept of “mehr”. In the “bon“(essence) of his existence lies the hidden treasure (“kanj”) which relates him to all other men and gives him the potential to become part of “jan” in his role as human being. He is invested with the faculty of co-ordination of his senses and sensations which makes him active and dynamic. Here the notion of “arkeh” (lit.: nave of a wheel) is particularly relevant. The abundance of his creative energy is kept in check through “trial and error”. He has to try himself to find out who he is and where his individual limits are.

As social being Iranian man realizes the values of “mehr” with the help of his ”kherad-e samandeh” (co-ordinating reason). For him creativity, love and care are at the root of any social order and not primarily the law. The ancient Greek idea of “nomos” i.e. the unrelenting divine or human law or the Islamic shari´a (Islamic law) is not Iranian thinking. Iranian man is anarchic by nature but in the most positive philosophical sense. He celebrates life in so many feasts (“jashn”) related to the seasons of the year i.e. he follows the natural rules around him, and then he adds his own, man made ones by a method of “hamporsi” (dialog) in which all members of society participate. When Iranian man uses his “kherad-e samandeh” to establish law and order he actually only provides a framework for creative activity.

In Iranian culture the “bunch of grapes” is an image which stands for mankind. Iranian people see themselves as part of the whole world. All individuals are related to one another just as the vine-berries carrying the “seeds” are attached to one another by the little wooden parts of the bunch. When seen as unity of all potential seeds the bunch of grapes (“khusheh”) symbolizes the divine.

Still today any Iranian child makes his first unconscious acquaintance with “mehr” and related concepts through the Simorgh from the stories of Firdausi's “Shahnameh”. The huge beautiful bird saves Zal's life, the royal child deserted by its parents, by acting as his wet nurse and later protects the hero Rostam, Zal's son, during his adventures. The name Rostam goes back to the old Iranian linguistic root “rao-takhma” which means “…a “seed” which grows and becomes visible and green by its own force…”.

M.Jamali's research into the Iranian way of thinking began with Firdausi's Shahnameh. He has defined and analysed the abstract concepts behind the colourful figures and stories of this epic work and gradually re-discovered the “Farhang-e Simorghi”. He followed up theses ideas going back in time as far as literature and archaeological finds permit. He demonstrated that Zoroastrianism and dualistic thinking are only a by-product of Iranian culture and perhaps not even a felicitous one. The mainstream of Iranian culture was “Farhang-e Simorghi”, a way of life so fit for survival that after the conquest of the Arabs in the seventh century A.D. a new full-fledged Iranian language emerges in the tenth century A.D. and becomes the carrier of the “Farhang-e Simorghi” in the guise of the Iranian epics, mathnawis and lyric poetry. In the same way as he went back in time M. Jamali now moves forward and Attar, Maulawi and Hafiz etc. have to yield their hidden knowledge about the “Farhang-e Simorghi”. Bit by bit M. Jamali's understanding of the Simorgh culture is becoming more lucid and complete.

M. Jamali's writings are seductive, especially when in his line of argument he is quoting from classical Persian poetry and the magic beauty of these poems flows into the text. A certain unexpected directness with which the author states his opinion about a problem at the beginning of his expositions captivates immediately the reader's mind, and then the vividness and originality of the following ideas are so impressive that one surrenders oneself completely and without hesitation to this fascinating world of Iranian thought and culture. To set out his ideas M. Jamali has chosen a peculiar style of meandering from theme to theme and subject to subject and obviously it is a marvellous way to do justice to the complexity of his thinking. Foreign literature he uses for stimulation only and just to give an impetus to a certain idea so that it puts his own train of thought in motion. The ancient Iranian values adapt themselves with ease to his manifold concepts about a modern Iranian society and his readers are reacting with enthusiasm. They already called him the “Firdausi of today”, the “Gandhi of Iran” and even the “Father of the new Iranian culture”. Many years ago during an encounter between the two M. Jamalzadeh characterized him as: “…mardi ba neshat…” (a man of a happy disposition).

A secular state, human dignity, none-violence, freedom and creativity, plurality and equal rights for minorities, variety and diversity, integration instead of punishment, democratic, anti-authoritarian government, an open society which cares for its members and takes part in the international efforts to find answers to global challenges – ideas which the young Iranian intellectuals discover in M. Jamali's books as something which their Iranian culture always possessed but which lay dormant for centuries underneath a blanket of Islamic believes. M. Jamali inspires new hope within the young generation in Iran and with his “Farhang-e Simorghi” shows a peaceful way out of the disastrous situation which the atrocities of Khomeini's regime produced for their beloved country.

( Bea Burgwinkel, 2007 )'